Baroque for days, darling

Disarming Masculinity - Oil on linen, 2022, 18” x 14” (reserved)

“So … is he effeminate?” is the first question my mother asked me when I told her that I was seeing a new guy. It was very matter of fact: in the same way that you would ask if someone wears glasses or has brown hair. There was no disdain in her voice. It’s simply what you ask when your son is gay. My inner child immediately answered with an emphatic no, but I did not. Instead, I smiled, and I asked her if she had ever asked my brother if his girlfriend was butch or manly. She produced a laugh and replied with an assertive, almost ridiculous, “no!” She did not understand why I would ask such an absurd question and she was growing impatient. Having just answered my question, she awaited my answer to hers, “so … is he effeminate?”

My recent work explores the cultural and artistic representations of gender through gay male subjectivity. As a portrait artist, I figured what better place to start than social media and painting gay male selfies. I was fascinated as to how gay men chose to represent themselves to a wider audience. For the most part, they are shirtless or fully nude reflections of their muscled bodies. You rarely have “average” or effeminate looking men. They present themselves as virile gym buffs that clench their teeth and push their jaws forward in an attempt to look as impossibly “masculine” as possible. They are the aesthetic embodiment of straight males. These are the same men that unwillingly spent their entire young adult lives suppressing their feminine predilections. Being “effeminate” threatened their very safety. The lack of traditional masculinity could be the reason they were bullied and ostracized. It is their limp wrists, obsessions with Barbie and dressing up or their fascination with female icons that could “out” them. And so, they learned very quickly to act like the other boys around them, suppress any interest in non-heteronormative practices and learn to hate all feminine aspects of themselves precisely because it is dangerous to exercise them.

“We’ve had to be good at disguise, at appearing to be one of the crowd, the same as everyone else. Because we had to hide what we really felt (gayness) for so much of the time, we had to master the façade of whatever social set-up we found ourselves in we couldn’t afford to stand out in any way, for it might give the game away about our gayness. So we have developed an eye and an ear for surfaces, appearances, forms: style.” (Dyer)

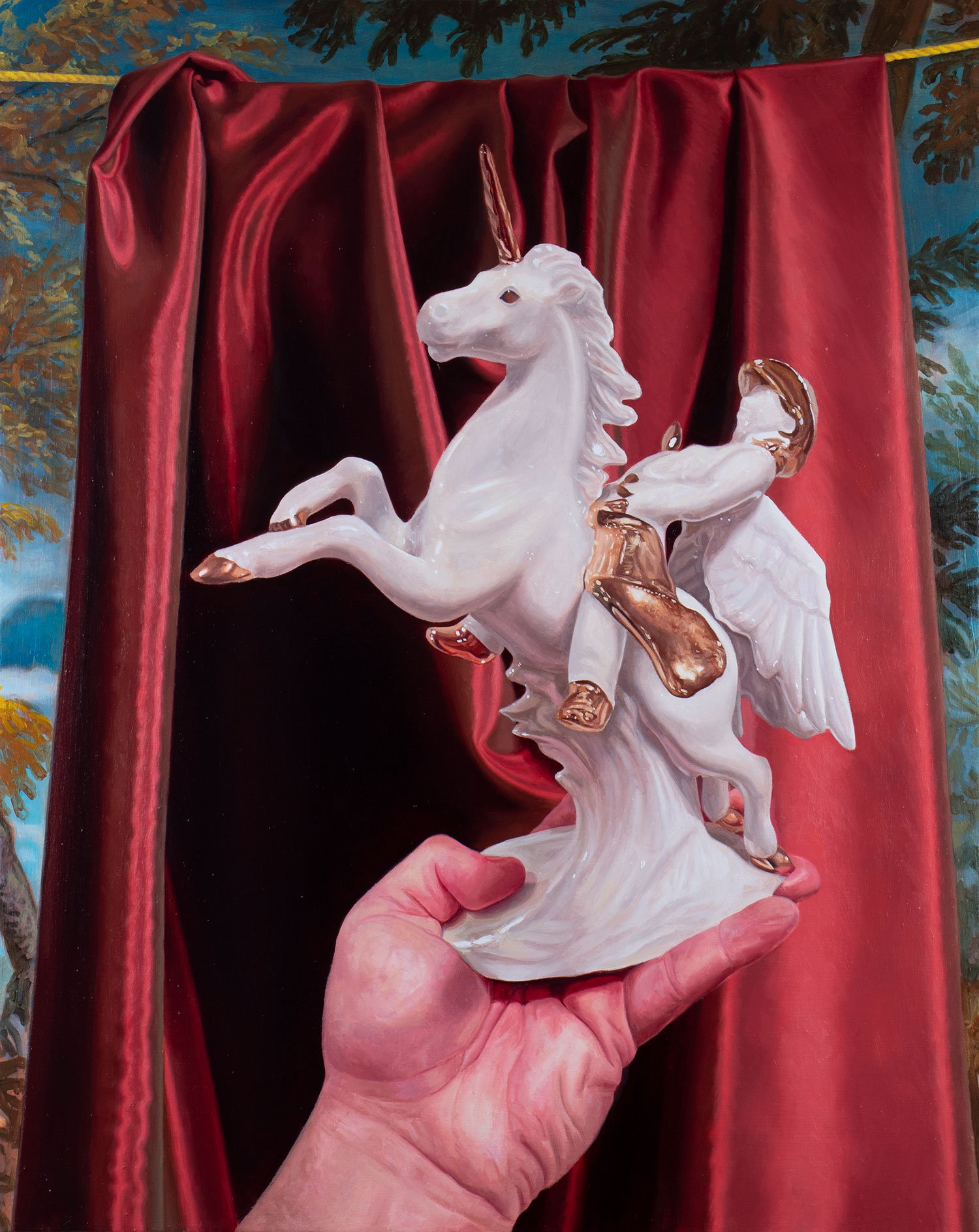

My interest then veered towards this idea of style and “queer sensibility.” Years before a child reaches sexual maturity, one can easily pick out the little boys that gravitate towards certain forms of “queer sensibility”: Listening to Celine Dion on repeat, arranging, categorizing and cleaning their rooms or exercising a strong interest in women’s fashion and even wearing heels. This has nothing to do with sexual attraction but everything to do with the idea that queer culture is indeed a culture of aesthetics, design and beauty. It isn’t surprising that gay men’s spaces and interiors tend to be extravagant or over the top. Because of the childhood suppression of all feminine qualities, and the social imposed wearing of straight drag, gay men create safe spaces adorned with objects, glamour and kitsch. Tableaux of a sort that express their feminine identity in the safety and privacy of their own homes.

This idea that gay men, their objects and spaces historically hold “queer sensibility” is precisely what I strive to paint and represent. I also think that I naturally gravitate towards highly rendered baroque like techniques because of an inevitable fascination with beauty and form. From romantic and literal depictions of limp wrists, I paint male hands that express tenderness, affection and fondness. I strive to blur the lines of non-gender conformity and create images that celebrate feminine depictions of men and their objects.

We stand on the precipice of change. With gender fluidity and non-binary acceptance. Why are certain traits, tendencies or objects socially coded as unmanly or effeminate? How do traditional concepts of masculinity affect queer sensibilities like beauty, glamour and camp? How do these concepts contribute to homophobia, stereotyping, and the devaluation of these sensibilities?

Coming back to my mother’s question: How a woman can hold such prejudice and ask such a question baffles me, in the same way that some of the most homophobic men I have met have been gay men. We fear in ourselves what we hate most in others and we’ve been historically programmed to despise women and womanly attributes. So engrained within systemic misogyny, my mother’s fear of my boyfriend’s effeminate nature is in some defective way, a protective fear, the same fear I held as a young boy of being found out, of being obviously gay to others, of being in harm’s way. At the end of the day, the active continuing battle for women’s rights and the acceptance of feminine qualities is the redeeming equation for the acceptance of “queer culture.”

Romantic Offering - Oil on linen, 2022, 18” x 14” (SOLD)

Tattooed Venus - Oil on panel, 2022, 20" Tondo

Delicate Clutch - Oil on linen, 2022, 30" x 24”

Gay Venus - Oil on panel, 2022, 20" Tondo (SOLD)

Mythical Fagtasy - Oil on linen, 2022, 30" x 24”

The Offering - Oil on paper, 2022, 12" x 16"

The Gift - Oil on linen, 2021, 24" x 34"

Nature's Gift - Oil on linen, 2021, 12" x 16"

In The Beginning - Oil on panel, 2022, 16” Tondo

Infinite Jest - Oil on linen, 2022, 18” x 14”

Undressing Masculinity - Oil on linen, 2022, 40" x 30” (SOLD)

Where it all Started - Oil on linen, 2022, 20" x 16”

Kitschy Kitty - Oil on paper, 2022, 12" x 16"

Forever Fresh - Oil on paper, 2021, 12" x 16"

Bedtime Cleansing Ritual - Oil on linen, 2021, 60" x 72"

ABOUT IAN STONE

As a child, I remember gravitating towards certain objects: beautiful, stylish, kitschy objects. I spent a large portion of my childhood at my grandparents’ house, filled with dusty tchotchkes and elegant Victorian antiques. I squandered hours alone with these other-worldly objects, developing a sensibility for decorative camp.

I would run my finger along a pair of bronze horses or satin lampshades and watch the dust lift and settle atop a porcelain ballerina figurine below. I would arrange and rearrange a collection of plastic fruit in a wicker bowl, discovering endless configurations. The ultimate fantasy was imagining how I would dis- play this collection of (seemingly) invaluable heirlooms in my someday home. I now own these objects, and I have found a home for them in my painting.

Ian Stone’s interest and exploration with painting began after his BFA in traditional Printmaking from NSCAD in Halifax, Nova Scotia. With a strong interest in self-portraiture and identity politics, the technical aspect of layering and printing was transferred to a figurative realism. He continued his studies at Concordia University with an MFA in painting and drawing. His work can be found in numerous private and public collections, including the Florida State University Museum and the National Palace of culture in Sofia, Bulgaria.